8 June 2021 year in the Chernihiv Historical Museum. VV Tarnovsky held a museum meeting "Where I throw a whip, I will go there with a doctor of historical sciences, Professor Serhiy Lepyavko, dedicated to the anniversaries of the uprising of Krzysztof Kosinski (430 years), Severina Nalivajka (428 years) and the Khotyn War (400-anniversary).

During the meeting, students learned the history of the professor's interest in the Cossack wars of the late XVI century., which has been decisive for his entire scientific career. Serhiy Lepyavko noted, that when he developed this scientific subject, then found 200 documents directly related to the K uprisings. Kosinsky and S.. Pour. Of particular interest among these documents is the so-called "Confession of Nalyvayka" found by him in the Polish historical archives in the town of Kournik near Poznan.. This document contains the transcript of the interrogation of C. Pour, which was held before the execution. The scholar highlighted the important information available on the history of the uprising. It is interesting, that among the issues of C. Pour, put during the interrogation, there was also the question of Prince Constantine of Ostroh, whose servant he was for some time. During the uprising of C. Nalyvayko and Prince Ostroh adhered to mutual neutrality, which aroused quite fair suspicions in the nobility about the integrity of the latter. However, until his death he denied the prince's involvement in the uprising. In general, Serhiy Anatoliyovych emphasized that, that during "Nalyvayko's reign in volosts" he tried not to harm and not to overload locals with accommodation and food of his army. Therefore, the rebels from time to time moved from one settlement to another. The quotation given in the title of the museum meeting taken from the document of that time fully reflects the thesis stated by the professor and was a direct answer of C. Nalyvayka on the question of the direction of movement of his military forces. The leader emphasized, that a more specific answer could be dangerous for him. This remark is quite correct given the spies.

Regarding the uprising of K.. Kosinsky, then the professor outlined his reasons, appealing to those granted under the Polish King Stefan Batory in 1582 Dr.. Cossacks privileges (personal freedom, inviolability of land and property, tax exemption), which were not finally enshrined in the legislation of the Commonwealth. Therefore, Cossack land awards and property were not protected by law. Accordingly, when a large magnatery, that is, the princes of Ostroh, began to extend its power to the Ukrainian lands and seize the property of the Cossacks and the petty local nobility, an uprising led by K. Kosinsky, who was also a nobleman, and the Cossack hetman. Professor, adhering to the "boyar" theory of the origin of the Cossacks, emphasized that, that the core on which the Cossacks held was the local Russian nobility and military people, who failed to prove his noble origin and corresponding status. Speaking on behalf of the Cossacks, such people tried to obtain or confirm the relevant privileges. So no wonder, that the uprising was supported by local nobles.

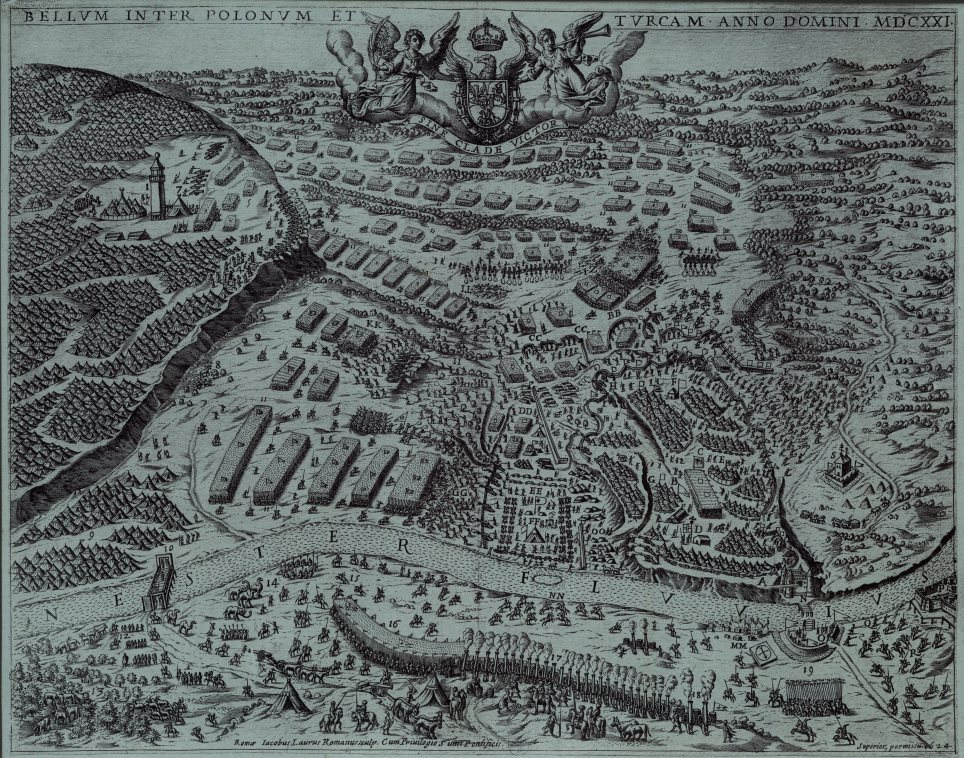

С. In his story, Lepyavko also touched upon the Khotyn War, pointing out the peculiarities of the weather conditions at that time, which significantly influenced the course of hostilities. The rain soaked stocks of gunpowder and firearms, which often made it impossible to use artillery during combat. The historian also noted the exceptional importance of the Cossacks for hostilities during the Khotyn War. He focused on that, that the Cossacks were equal in number to the Polish army and were equipped with military equipment no worse than the Poles. This fact, according to the historian, testified to the self-sufficiency and viability of the Ukrainian Cossacks, which grew out of the constant struggle with the Tatars. The formation of the Hetmanate became a logical continuation of the struggle of the Ukrainian Cossack elite for their rights and freedoms granted under the privileges of King S. Batory.

During the meeting, the guests were also shown the exhibition "Ukrainian Cossacks between the Commonwealth and the Ottoman Empire". Unique items directly related to the military-historical events of the late 16th and early 17th centuries were shown. You could see a whip at the exhibition, which according to legend belonged to S. Nalyvayko. It was transferred to the Chernihiv Provincial Academic Archival Commission from the Oster clerk 1899-1900 рр.

One of the exhibits, which attracted the special attention of museum guests, was a Polish saber blade of the second half of the XVI - early XVII centuries. On the blade is a silver image of the King of the Commonwealth Stefan Batory (1576–1586) with the inscription: «STEPHAN BATORY REX POL[oniam]»("STEFAN BATORIY KING POL[YES]»). On the reverse side of the image of the Mother of God and, mostly, damaged inscription in Latin. The portrait of the ruler on the blade was a mandatory part of the tradition of creating so-called memorial sabers. Each such weapon was characterized by its own typological image of the ruler and a number of other features according to which the types of sabers were called. In this case, the so-called "bator" was presented in accordance with the signature and portrait of the king. Such sabers were common from the second half of the XVI - to the middle of the XVIII century. on the territory of the Commonwealth, particular, and in Ukraine among the Ukrainian nobility. Also this tradition, to a certain extent, was adopted by a Ukrainian Cossack officer on the blades of a saber which depicted Ukrainian hetmans.

Among the interesting exhibits of the exhibition, the museum guests noted the shock-flint pistol of the XVII century. made in Spain.

Another item in the museum collection, which aroused great interest, was a scythe - a special type of personal weapon of the corps of professional infantry of the Ottoman Empire, тобто, Janichar. It is characterized by a blade with reverse bending and sharpening on the inside of the arc. The length of the blade of the demonstrated specimen 68 see. The scythe handle is usually made of bone, horns, metal and wood with extension, actually a wrist rest, in the form of ears or less horns. This design prevents the sword from slipping out of the warrior's hand. The scimitar presented to visitors has a simple design, without precious jewelry, which certifies the property status of the owner and his purely utilitarian military purpose. Swords were common not only in the Ottoman Empire, but also geographically close to it territories and countries under the Turkish protectorate (Crimean Khanate, Balkans, Middle East, Кавказ). The scimitar dates back to the XVII-XVIII centuries.

Researcher,

Candidate of Historical Sciences Valentin Rebenok

More Stories

To the 135th anniversary of the archaeologist Petro Smolichev

Path to Unification

Results 2025 year